Historical Notes on The Plague and Fire of London

Background Information

Charles 11 and the Queen

The Queen was Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess who brought with her Tangiers as a dowry. The marriage was not a successful one, although the King and Queen continued to live together reasonably amicably despite Charles's many infidelities. Unfortunately, the marriage remained childless, a fact that was to generate much future trouble, as it left Charles's brother James, Duke of York, as heir to the throne.

Charles's competence as both a political manager and national leader are very much open to debate. Some have seen him as a wily and astute, if unscrupulous, manipulator both of public opinion and of the political scene; others have characterized him as one who merely staggered from crisis to crisis, succeeding, ultimately, more by dint of good luck than by ability.

On a personal level, Charles could evidently be a delightful companion: witty, generous, and immensely accessible, he charmed both the members of his own court, and, more surprisingly, the common people, with whom he never lost his enormous personal popularity. He could be very gentle and compassionate: while his numerous amours and the high public profiles maintained by many of his mistresses were doubtless an enduring humiliation to his queen, Catherine of Braganza, he seems to have had real affection for her

In short, this Prince might more properly be said to have gifts than virtues, as affability, easiness of living, inclinations to give, and to forgive: Qualities that flowed from his nature rather than from his virtue.

He was very charming, softly spoken and not very bright. He dressed ostentatiously with lots of lace and diamond buckles.

|  |

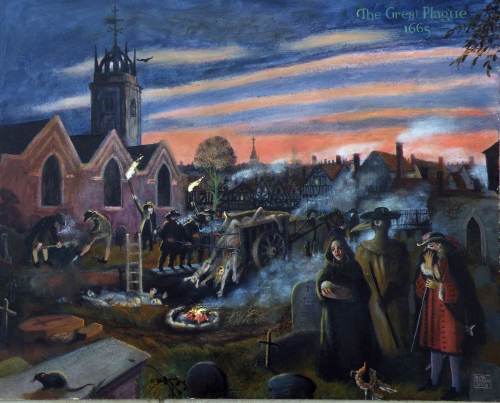

The Great Plague

Roughly 150 million individuals succumbed to the nightmarish symptoms of the Black Plague.

First, swollen lymph nodes would signal infection. Within days, these painful buboes would blacken and then burst, spewing forth pus and blood. Dark purplish patches all over the body were par for the course. The lucky ones would recover, while others would soon go on to suffer high fever and agonizing episodes of spasmodic pain, vomiting and retching while blood sometimes filled their lungs. For the fortunate, death would come quickly; others lingered in a state of delirium for days.

Panic, desperation and grief reigned supreme, from the humblest burgs to the most vibrant cities throughout Europe. All manner of prayers and bargains and cures were attempted, but to no avail. With no antibiotics available to fight the dreaded bacteria, the plague would simply have to run its course. The plague did not entirely disappear from European soil until the 19th century as smaller but still deadly outbreaks occurred continuously in the decades that followed.

The Plague Doctors

Once the plague’s full force was felt, it didn’t take long for most reputable and well-trained doctors to recognize its vicious and virulent nature. Moreover, any physician with even a lick of sense soon realized that the "cures" being employed were anything but, and sometimes even accelerated the death spiral, most of them ran away. It was really the only sensible thing to do.

Those who took their place — the so-called plague doctor were often little more than paid hacks and second-rate physicians hired by desperate municipalities. These eerily clad public servants would become an iconic symbol of the plague that we easily recognize to this very day... harbingers of doom in a very dark chapter in the history of human suffering.

To say people didn’t know much about the plague was an understatement. From its origins, to its spread, to its cure, the physicians whose sole purpose was to treat this infamous killer knew little more than those whom they were treating. They did, however, understand one thing with perfect clarity: the fact that it spread quickly and easily. Desperate times called for desperate measures.

Poultices of onion and butter, sprinklings of dried frog, arsenic, floral compounds and even a generous bloodletting or two were no match for this killing machine. The closer the patient was to dying, the more desperate the cures became. Accounts exist of coating sufferers in mercury and baking them for a while in the oven, though this was likely not as unpleasant as some of the creative means by which diarrhea was induced to relieve the patient’s system of the invading demons. Those with no medical training were often even more creative in their attempts to cure.

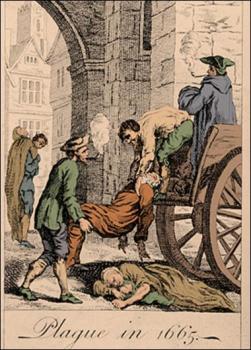

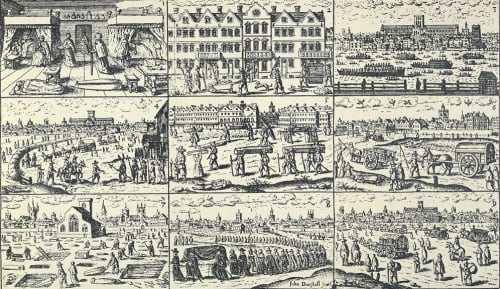

Nothing worked to halt the spread. The bodies piled up quickly and were carted away, dumped unceremoniously into mass graves. Hundreds were burned at a time. Entire villages succumbed and simply ceased to exist. Coping the best they could, the living often went crazy with fear, committed suicide, threw themselves into all-consuming religious devotion or indulged in a Bacchanalian end-of-days-style orgies that would have made Caligula blush. Murderers and thieves were let out of jail on the condition they agree to help with the removal and incineration of bodies.

Presumably, their principal task of the plague doctors was to help treat and cure plague victims, and some did give it their best shot. In actual fact, however, the plague doctors’ duties were far more actuarial than medical. Most did a lot more counting than curing, keeping track of the number of casualties and recorded the deaths in log books.

Plague doctors were sometimes requested to take part in autopsies, and were often called upon to testify and witness wills and other important documents for the dead and dying. Not surprisingly, many a dishonest doc took advantage of bereaved families, holding out false hope for cures and charging extra fees (even though they were supposed to be paid by the government and not their patients).

Then, as now, it seems a life of public service was occasionally at odds with the ambitions of some medically minded entrepreneurs. Whatever their intentions, whatever their failings, plague doctors were thought of as brave and highly valued; some were even kidnapped and held for ransom.

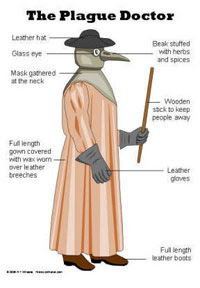

COSTUME

The plague doctor was a terror to behold, thanks to his costume — perhaps the most potent symbol of the Black Death. as a carefully considered way to protect himself from having to visit powerful, plague-infested patients he couldn’t say no to the costume quickly became all the rage among plague doctors throughout Europe.

Made of a canvas outer garment coated in wax, as well as waxed leather pants, gloves, boots and hat, the costume became downright scary from the neck up. A dark leather hood and mask were held onto the face with leather bands and gathered tightly at the neck so as to not let in any noxious, plague-causing miasmas that might poison the wearer. Eyeholes were cut into the leather and fitted with glass domes.

As if this head-to-toe shroud of foreboding wasn’t enough, from the front protruded a grotesque curved beak designed to hold the fragrant compounds believed to keep “plague air” at bay. A wooden stick completed the look, which the plague doctor used to lift the clothing and bed sheets of infected patients to get a better look without actually making skin-to-skin contact.

The mask had glass openings for the eyes and a curved beak shaped like that of a bird. Straps held the beak in front of the doctor's nose. The mask had two small nose holes and was a type of respirator which contained aromatic items. The beak could hold dried flowers (including roses and carnations), herbs (including mint), spices, camphor, or a vinegar sponge. The purpose of the mask was to keep away bad smells, which were thought to be the principal cause of the disease in the miasma theory of infection, before it was disproved by germ theory. Doctors believed the herbs would counter the "evil" smells of the plague and prevent them from becoming infected.

The beak doctor costume worn by plague doctors had a wide-brimmed leather hat to indicate their profession. They used wooden canes to point out areas needing attention and to examine patients without touching them.[8] The canes were also used to keep people away to remove clothing from plague victims without having to touch them, and to take a patient's pulse.

This outfit probably did very little to quell the actual spread of the disease. The beak doctors, as they came to be know, dropped like flies or pretty much lived under constant quarantine, wandering the countryside and city streets like pariahs... until of course desperate families needed them.

Samuel Pepys

MP and chief secretary to The Admiralty. Like many men of small stature he was assertive and commanded respect. He was a good administrator and famous diarist. In the musical, he is slightly portly, dapper, very ambitious and a bit pompous.

John Evelyn MP and diarist

Educated in Europe, he had made himself prodigiously learned, not only in classical literature but also in scientific and technical matters. He soon established himself as one of the foremost virtuosi of his day.

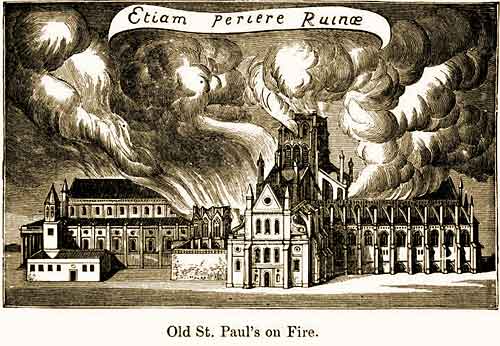

The fourteen years following the king’s return were those of Evelyn’s greatest public activity, although the offices he held were only temporary appointments. He served on several commissions from 1660 to 1674—for the improvement of London streets in 1662, for the Royal Mint in 1663, and for the repair of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1666, during which he worked with Christopher Wren. On 13 September 1666 Evelyn presented his plan for the rebuilding of the city, together with a discourse on the problems involved

Christopher Wren

showed an early talent for mathematics and enjoyed inventing things, including an instrument for writing in the dark and a pneumatic machine. In 1657, Wren was appointed professor of astronomy at Gresham College in London and four years later, professor of astronomy at Oxford. In 1662, he was one of the founding members of the Royal Society, along with other mathematicians, scientists and scholars, many of whom were his friends.

Wren's interest in architecture developed from his study of physics and engineering. In 1664 and 1665, Wren was commissioned to design the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford and a chapel for Pembroke College, Cambridge and from then on, architecture was his main focus. In 1665, Wren visited Paris, where he was strongly influenced by French and Italian baroque styles.

In 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the medieval city, providing a huge opportunity for Wren. He produced ambitious plans for rebuilding the whole area but they were rejected, partly because property owners insisted on keeping the sites of their destroyed buildings. Wren did design 51 new city churches, as well as the new St Paul's Cathedral. In 1669, he was appointed surveyor of the royal works which effectively gave him control of all government building in the country. He was knighted in 1673.

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke is one of the most neglected natural philosophers of all time. The inventor of, amongst other things, the iris diaphragm in cameras, the universal joint used in motor vehicles, the balance wheel in a watch, the originator of the word 'cell' in biology, he was Surveyor of the City of London after the Great Fire of 1666, architect, experimenter, worked in astronomy - yet is known mostly for Hooke's Law. He fell out with Newton, and certainly had a difficult temperament. He deserves more from History than he received in his lifetime.

Hooke the Architect

While working as a scientist, Hooke developed a sideline career as an architect. People liked his designs for buildings, and he was appointed to be Surveyor to the City of London. In fact, he made much more money as an architect than as a scientist, because he designed many of the buildings which replaced those destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Bargees

They had a guild and a monopoly and shamefully took advantage of the fleeing people in the fire.They were the only people allowed to operate on The Thames. They were a rough lot of rogues, poorly educated and open to the main chance. They rowed people over the Thames and to ships as well as goods. Their boats had sails and oars.

Locksmiths- There was a guild of locksmiths called Lockyers. They made complex locks of exquisite designs. Probably when the plague was at its height, they would not have used such expensive devices and merely nailed a piece of wood or steel , with a padlock, onto the doors of houses to prevent people from getting out.They locked up whole families , the well along with the sick, who caught the disease so many died unnecessarily.

Watchmen were an early form of policing performed by private individuals

From the 1730s local improvement Acts often included provision for paid watchmen or constables to patrol towns at night, while rural areas had less formal arrangements.

Night watchmen patrolled the streets between 9 or 10 pm until sunrise, and were expected to examine all suspicious characters. In the City of London, daytime patrols were conducted by the City Marshall and the beadles. Like the night watch, their primary responsibilities were to apprehend minor offenders and to act as a deterrent against more serious offences.

By the end of the century, however, it was becoming clear that these local forms of policing, which varied in effectiveness from town to town, were hardly adequate in the sprawling new industrial districts.

17th century Civil War, meant that the country was highly suspicious of soldiers and loathed the idea of a special force of lawmen. This left a large part of crime prevention up to the individual. If you were robbed, you had to find out who did it and take the person to court yourself.

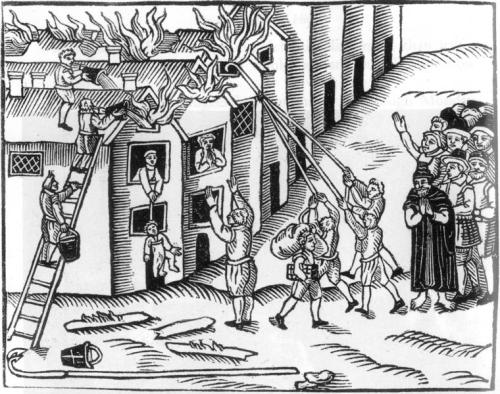

The Great Fire of London was a disaster waiting to happen. London of 1666 was a city of medieval houses made mostly of oak timber. Some of the poorer houses had walls covered with tar, which kept out the rain but made the structures more vulnerable to fire. Streets were narrow, houses were crowded together, and the firefighting methods of the day consisted of neighborhood bucket brigades armed with pails of water and primitive hand pumps. Citizens were instructed to check their homes for possible dangers, but there were many instances of carelessness.

So it was on the evening of September 1, 1666, when Thomas Farrinor, the king's baker, failed to properly extinguish his oven. He went to bed, and sometime around midnight sparks from the smoldering embers ignited firewood lying beside the oven. Before long, his house was in flames. Farrinor managed to escape with his family and a servant out an upstairs window, but a bakery assistant died in the flames--the first victim .of the Fire

Sparks from Farrinor's bakery, leapt across the street and set fire to straw and fodder in the stables of the Star Inn. From the Inn, the fire spread to Thames Street, where riverfront warehouses were packed full with flammable materials such as tallow for candles, lamp oil, spirits, and coal. These stores lit aflame or exploded, transforming the fire into an uncontrollable blaze. Bucket-bearing locals abandoned their futile efforts at firefighting and rushed home to evacuate their families and save their valuables

It had been a hot, dry summer, and a strong wind further encouraged the flames. As the conflagration grew, city authorities struggled to tear down buildings and create a firebreak, but the flames repeatedly overtook them before they could complete their work. People fled into the Thames River dragging their possessions, and the homeless took refuge in the hills on the outskirts of London. Light from the Great Fire could be seen 30 miles away. On September 5, the fire slackened, and on September 6 it was brought under control. That evening, flames again burst forth in the Temple (the legal district), but the explosion of buildings with gunpowder extinguished the flames.St Clemens Church

In the Summer of 2015 a production of The fire of |London screen play was shown on TV-a good source for costume ideas

Baker’s cart 1656